Macedonia

MACEDONIA

“There are peoples that owe their identity to a country, and countries that owe their identity to a people. If the Americans are the product of America, Macedonia, by contrast, is nothing more than the country of the Makedones. Hence the difficulty in defining it precisely in geographical terms. Throughout history, the boundaries of the country have followed the expansion of the Macedonian people, from the Pindus range in the west to the plain of Philippoi in the east, and from Mount Olympus in the south to the Axios gorge, between mount Barnous (Kaimaktsalan) and Orbelos (Beles) in the north”. (M. B. Hatzopoulos, Macedonia from Philip II to the Roman Conquest, Athens 1993, p. 19.)

THE MACEDONIAN KINGDOM

The founding of the Macedonian kingdom is lost somewhere in the realms of myth. Traditions concerning its early history are found in the work, among others, of Herodotos (8.136-139). According to his version of the legend, three brothers from Argos, Gavanes, Aeropos and Perdikkas, travelled through the land of the Illyrians to Levaie, a town in “Upper Macedonia” (as the mountainous region of western Macedonia was referred to in antiquity).

From there, they crossed the Aliakmon River and settled in the fertile grasslands, where they established their kingdom with Aigai (modern Vergina) as its center. This kingdom gradually expanded as the early Macedonian kings drove away the Thracians who inhabited the area, forcing them to settle east of the Axios River (Thucydides 2.99.3-6). Originally, the Macedonian kingdom included only “lower Macedonia, or Macedonia-by-the-Sea” as the fertile plain west of the Axios River was called, confined by the mountains of Olympos, Pieria, Bermion and Barnous, and the Thermaic Gulf.

The royal family of the Temenids originated in Argos and ruled the Macedonians, one of the Greek tribes of the North, related to the Thessalians and the Epeirotes. The history of Macedonia has been a continuous effort to incorporate and absorb peoples of different origins and traditions and at the same time repel dangerous and aggressive neighbors, especially from the Balkans. Even after the conquest of Macedonia in 168 BC, the Romans were obliged to keep forces along the borders in order to control invasions.

The colonies that the city-states of southern Greece, the Aegean islands and Ionia had founded on the coasts of Pieria, Chalkidike and Thrace, were immediate neighbors of the Macedonians and influenced them in several ways, including the minting of coins. Macedonia’s relations with the greatest political powers of the South, Athens and Sparta, were one of the most important aspects of the kingdom’s foreign policy. Rivalry for control of the resources in the North, which the city-states of the South sought to exploit, in combination with Macedonia’s need to retain good relations with the Athenians, to whom they sold large amounts of Macedonian timber for the construction of their fleet, made it necessary for the Macedonian kings to exercise all possible diplomacy in order to preserve the sensitive balance of power.

After the weakening of the Athenians and Spartans, Macedonia took over the role of leader of the Greeks, and Alexander, Philip’s son, led them on a long military campaign in Asia, resulting in a complete political, economic and cultural transformation of the known world. The creation of the Hellenistic world, due to the fusion of Greek culture with the ancient cultures of the East, was the greatest contribution of the Macedonians to world history.

THE ECONOMY

The Macedonian economy was originally based on nomadic stock-breeding. This fact is also mirrored in the legends about the kingdom’s founding. According to these legends, the three founders of the Macedonian kingdom were stock-breeders: the first bred horses, the second cows and the third sheep and goats. According to one of the legends, one day the third and youngest brother wandered off, following his herd, to the foothills of the Pieria mountain range and settled there. The place was thereafter named Aigai (“the land of the goats”) and became the kingdom’s capital city.

However, stock-breeding was not the only economic activity of the Macedonians. The fertile alluvial plain of central Macedonia was highly suitable for the cultivation of grain, vegetables and fruit trees. The vineyards in the area of Pella produced renowned wines, and Chalkidike offered large quantities of olives, as it still does today. Nevertheless, the wealth of the Macedonian monarchy was mainly based on its mineral resources and plentiful timber. Copper, iron, silver and gold mines were royal property and yielded important income. The Macedonians' continual efforts to include and later retain Chalkidike and Eastern Macedonia in their state was partly due to the rich mineral deposits found there. The mining of large quantities of precious metals enabled the kings to mint coins for their kingdom; it also resulted in the development and flourishing of metallurgy and the working of silver. Metal artifacts produced by Macedonian craftsmen circulated within the kingdom and were exported as well.

Timber from Macedonian forests was high-quality material for ship building; economic and political relations between Macedonia and the greatest naval power of the time, Athens, were largely influenced by the production and export of Macedonian wood. Finally, control of the ports was another important source of income for the central government, which either received port tolls directly or rented out the function to tax collectors.

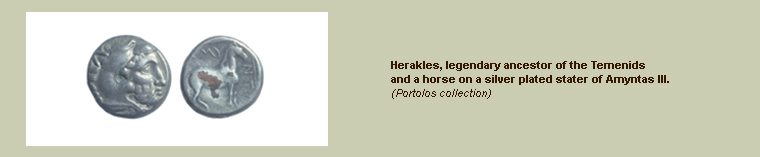

ROYAL COINAGE

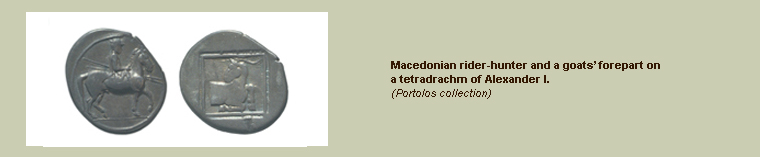

The cities and peoples of northern Greece, and especially of Chalkidike and eastern Macedonia, first minted coins during the last quarter of the 6th century BC. A few decades later Alexander I (498-454 BC) launched the first royal coinage. After the retreat of the Persians, taking advantage of the power gap, he extended his kingdom eastwards, bringing under his control the mines of Bisaltia, around Lake Prasias. According to Herodotos (5. 17. 6-10), those mines produced silver worth one talent per day.

Since its beginning, there was a tendency in Macedonia to distinguish coinage intended for use abroad and that intended for circulation within the kingdom. Both Alexander I and his son Perdikkas II (451-413 BC) issued tetrobols using two different weight standards and distinct iconographical types. Coins intended for export were made of purer silver and were heavier. The use of debased silver or the issue of coins of a lighter standard was typical of Macedonian coinage during periods of crisis and financial difficulty.

Following the practice of the cities of Chalkidike, late in the 5th century BC, Archelaos (413-400/399 BC) adopted the use of bronze coins for Macedonia. Those small- denomination coins were used for everyday transactions within the area where they were minted. Bronze coins replaced the small silver denominations which were unpractical, and at the same time helped the state save precious metals. The early introduction of bronze coins in Macedonia compared to most city-states in southern Greece, shows just how widespread was the use of money in everyday transactions.

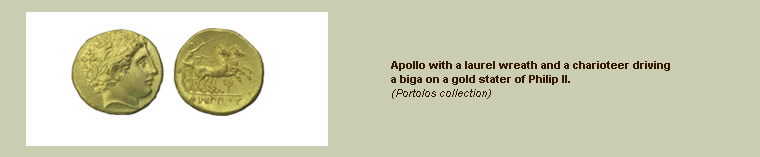

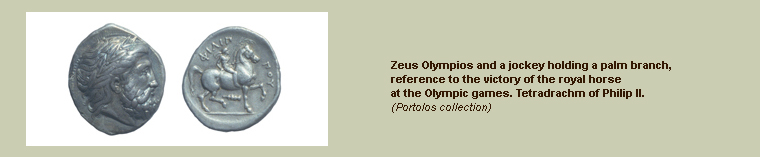

Macedonian coinage flourished under Philip II (359-336 BC). Crucial for this were the kingdom’s expansion eastward and its control of the mines. After abolishing the league of cities in Chalkidike, Philip followed their example and struck gold coins for the first time. These “philippeioi” spread widely all over the Balkan Peninsula and were greatly sought after for the purity and the high value of their metal, even among peoples much less familiar with the use of coins as money.

The fact that Balkan and central European peoples minted coins imitating the “philippeioi” for centuries is clear proof of this point. The same is true also for Philip’s silver tetradrachms, which penetrated the Balkan markets and continued to be issued for decades after his death.

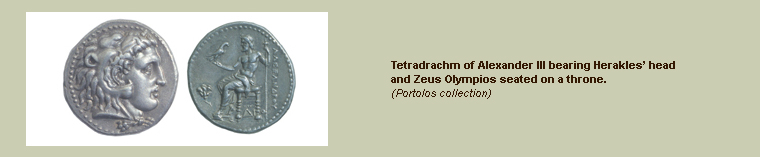

During Alexander’s reign (336-323 BC), the Macedonian tetradrachm penetrated the markets of the Mediterranean, displacing the “international” currency of the time, the Athenian “owls”. After the abolition of the Persian Empire with its centralized economy, and the capture of the vast royal treasures, Alexander was able to bring into circulation huge quantities of precious metal in coin form. Tetradrachms with the head of Herakles on the obverse and Zeus with the eagle on the reverse became extremely popular, and their production was continued by later Macedonian kings and by autonomous cities, especially in Asia Minor, the Peloponnese and Pontos, until the 1st century BC.

They were known as “Alexanders”, and in the collective consciousness of the public Herakles, the Temenidian dynasty’s mythical founder portrayed on them, was identified with Alexander himself.

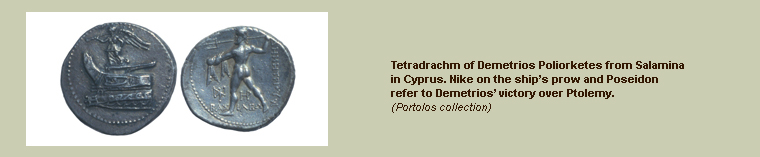

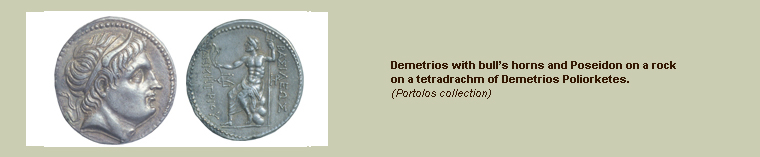

Alexander’s death was followed by a period of antagonism and conflict among the Successors, which led to the formation of the Hellenistic kingdoms. Demetrios Poliorketes (son of Antigonos, one of Alexander’s generals and founder of the Antigonid dynasty) minted coins in his possessions in Asia Minor and Cyprus. Most famous are the tetradrachms of Salamis in Cyprus, depicting Victory on a prow blowing a trumpet and Poseidon.

The iconography on these coins refers back to Demetrios’ important naval victory over Ptolemy near Salamis in 306 BC, after which he received the royal title from his father. As “king” of Macedonia (294-288 BC), and following the example of Ptolemy of Egypt, Demetrios was one of the first to put his own portrait on his coins.

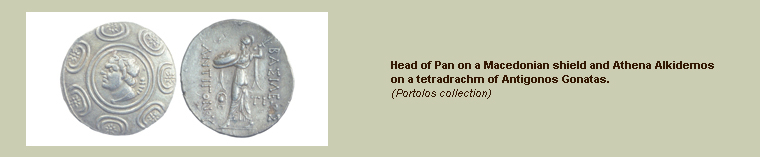

Demetrios’ son, Antigonos, who took over from his father a few years later (277/6-239 BC), managed to establish relative security and peace for the Macedonian kingdom after the long period of warfare in the wake of Alexander’s death. During his reign, coin production was extensive.

Not only did he continue issuing the Alexander- type tetradrachms, a very popular coin for the payment of mercenaries, but launched in addition two new tetradrachms that extended into the reign of his successors, Demetrios II (239-229 BC) and Antigonos Doson (229-221 BC).

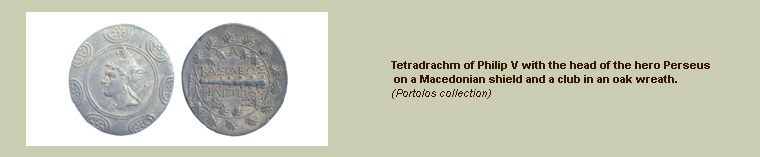

Philip V (221-179 BC), the son of Demetrios II, had to confront the new rising power in the Mediterranean, Rome.

Philip has been portrayed as one of the most controversial personalities in the history of Macedonia by historians who viewed him and the events of his reign in a definitely anti-Macedonian light. Although he came to power at the age of 17, he managed to secure Macedonia’s position in the Greek world, confronting the Aitolians, and at the same time tried to avoid the Romans’ intervention and defend his state against them. In the final years of his reign, he showed great dynamism, reorganizing the state and enhancing revenues, productivity and population growth. In this period, one can observe a major breakthrough in the numismatic history of Macedonia: the right to mint coins ceased to be an exclusively royal prerogative and was extended to the Macedonian commonwealth, the administrative units in which it was divided, certain cities and even some shrines.

Despite Philip’s great achievements, Macedonia’s fate could not be averted. His son, Perseus (179-168 BC), was defeated by the Roman army that invaded Macedonia from the West, and after the battle at Pydna (168 BC) his kingdom was abolished, and Macedonia came under Rome’s direct political influence.

The production of debased tetradrachms had been one of Perseus’ last efforts to deal with the financial burden of warfare, which eventually led to the kingdom’s abolition.

|

|

|